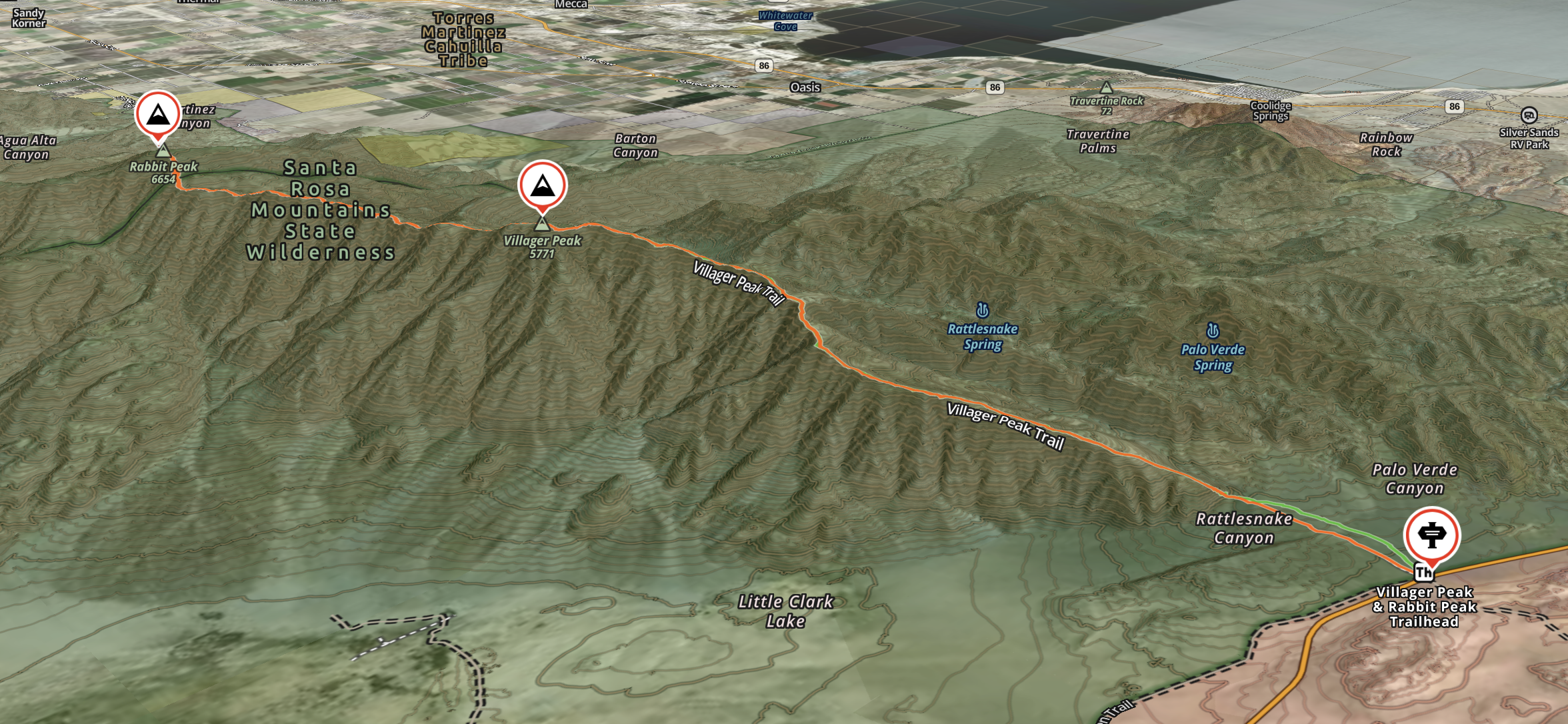

Villager Peak-Rabbit Peak, Anza Borego (HPS/DPS)

The way was not clear at first, and we tumbled forth across the rocky flats. The ocotillo were budding red at the tips in the heat of early spring. Ninety degrees, to be exact, which was not uncommon and yet was not expected. This made the route far more intimidating. The central question was How much water? Not only because Anza Borego hosted few perennial sources—and our route none at all—but also for the grave fact that a single liter of fluid, which could pleasantly be guzzled in a single draft, weighed two and a quarter pounds. And so the cost of life began to weigh on the back and lumbar and seem not altogether worth it.

We settled on five and a half liters per person, a grand sum that seemed reasonable if not entirely responsible. While spending the night en route would increase our water demands, we decided that no more than twenty-four hours would pass before we stood once more in the shade of our cars.

At two-thirty pm we set out for Rabbit Peak, which sits high on the enclosing range of the Clark Valley, a basin known for its ancient playa (or dry lake bed) whose blighted crust is every bit as impressive as Death Valley’s Badwater Basin. Local peaks are notorious for their inaccessibility: there is no easy route on offer, one must either descend the untrailed length of of the Santa Rosa Mountains from their northern terminus of Toro Peak—far more involved and rarely attempted—or submit to the exhaustive climb from the valley floor.

We opted for the latter and soon were trudging up the unforgiving southern slope. This would define our next two hours. Pleasant enough from a geological perspective, but downright brutal to the hiker. We gained 2,500 feet before the unending wall of marl yielded any view, and then another 2,000 feet along the ridgeline before it flattened. Here at last were patches of dirt level enough for a proper camp. Of course, there was nothing proper about our camp, for by then we had each consumed more than our rationed share of water, were thoroughly exhausted and, having enjoyed views to both sides of the ridge as well as a particularly memorable sunset, were centered firmly on the inevitable dehydration of the following day. Just south of Villager Peak we took shelter behind a sharp spine of rock and watched the dull glow of stars brighten the Salton Sea. We slept in various states of disrepair: one of us beneath a tarp, myself in an ultralite bivy, durable as Kleenex, and the last of us directly on the dirt, his pack positioned as a pillow. The heat of the day ebbed to a temperate night and sleep came easily, the early hours offering a deep twist of shifting stars.

We struck off at four am and summited Villager Peak for sunrise. The route, which up to this point was composed of a single element—that being unrelenting gain—here changed significantly. We were treated to the proverbial rollercoaster on which we rode land-bridges that spanned deep gullies to cross a series of unnamed peaks. The terrain grew lush as we approached Rabbit Peak, and we topped its broad summit before noon, which, while perfectly respectable given our tireless pace, was far later than we intended. Twin summits cap the peak, both easily mounted and but a thousand feet apart; one bearing the iconic pained sign and the other a bolted register. Sadly, the views do not compete with those of Villager Peak, but the wide, shaded plateau offers an ideal campsite for any so inclined.

And now the price came due—after the brief flash of glory that attends all human accomplishment quickly faded, we gazed at our sorry water stores and contemplated the long descent ahead. Yes, outside the countless bumps to be traversed between Rabbit and Villager, the return was largely downhill; and yes, the day did not have the same bite as the one prior, having cooled by some degrees; yet none of us were comforted. With the bleak fatalism of the condemned sharing a final smoke, we divvied up the remaining water so that each had roughly eleven-hundred milliliters and could not complain more than any other. And there was cause for complaint indeed: persistent headaches, abdominal spasms, and the myriad symptoms of moderate dehydration. We did not devolve to dizziness or incoherence, though there was a distinct shuffling to our progress, not unlike that of low-budget zombie movies, and we arrived at the cars having spent the last three hours passionately debating the merits of one flavor Gatorade over another.

It was here, having already endured the trial, that we decided to check its stats. According to many reports online, the Villager-Rabbit route is more demanding than “Cactus to Clouds,” the hiker’s badge of honor that climbs from the Palm Springs Art Museum to the summit of San Jacinto Peak, spanning nearly ten thousand feet of vertical gain along its course of twenty miles. The Villager-Rabbit route, however, is not merely a trial but also an indulgence: the sight of Clark Valley whirling beneath you, stretching to all directions, as you ascend will not be soon forgotten. Nor will watching Coyote Mountain (which from the basin floor appears tremendous) shrink to a minor heap of rubble. Nor will any element of a desert expedition—for in a region so vastly inhospitable, every journey, whether on- or off-trail, dayhike or backpack, of middling length or comprehensive, feels like a true expedition.

Though, in retrospect, it may be worth sacrificing a bit of this drama by carrying more water.

Summit: 5,771 ft

Distance: 22 miles

Elevation Gain: 8,439 ft

Total Moving Time: 17:02